“Mutti, Fatti, bitte kann Ich gehen?”

“Mommy, Daddy, please can I go?” Rosemary hoped her cries would distract everyone from the untouched liver and onions on her dinner plate. Werner looked kindly and lovingly at his princess. Lilo took a deep breath and began to scold her unruly daughter. Henry desperately willed the conversation to end so he could escape to grab a cigarette.

In 1955, the Bollmann family had been living in the United States for 8 years. Werner was planning his first trip back to Germany to visit his mother and to celebrate her 79th birthday. It would be an expensive endeavor. The family had worked very hard for the past ten years, especially Werner, who worked nights in a tool and die shop for Fisher Body.

Werner was uncertain what a trip to Germany would mean. Although he wasn’t the rebel of his family (that honor would be saved for his brother Paul), he was in the awkward position of having married Jew during the 1930s , while his brothers became members of the National Socialist party. He would rather forget life in Berlin during the war, and the Bollmanns were comfortable now with their life in Cincinnati, Ohio.

It had been his wife Lilo who encouraged him to make the trip to visit his mother. She herself did not care for her mother in law – the disdain for the daughter in law was mutual – but Lilo was a firm believer in family. “You need to see your mother again,” she had admonished a few months earlier.

Now, here was Rosemary, or Mady as she was affectionately known to the family, begging to go along. And Werner always wanted to make his princess happy.

“Alle anderen haben eine Grossmutter,” the little girl begged. All the others have a grandmother.

Lilo, who had grown up a princess in her own father’s eyes, was not happy to compete with Rosemary for Werner’s affections. While she had encouraged Werner’s travels, those of her daughter’s were a different story. The additional travel costs were not a welcome expense.

Henry also did not have fond feelings for his grandmother. As a child, he had been sent to live with her briefly during the war while Berlin was under attack. But as the son of a “mixed race” couple, he was a “Mischlinge”, a half-breed. And he was referred to as her “Jewish grandson” and taunted more in the German countryside than he had been in cosmopolitan Berlin. Where was that cigarette?

But Rosemary knew no family other than the three around the table. No aunts, no cousins, and certainly no grandmother or grandfather, as she was barely two years old when the family emigrated to America.

“Mutti, Fatti, bitte kann Ich gehen? Ich mochte meine Grossmutter treffen,” she begged. I want to meet my grandmother.

Choking down tears, she fought over every bite on her plate. Dinner always held so much drama, thought Henry, especially when Mady was served liver and creamed spinach for her anemia. No wonder he smoked.

There was more drama afterward as Lilo cleared the dishes. Lilo was accustomed to having her way. After all, she was the one who insisted they move to the United States, even though Werner was a partner in a booming reclamation business in the months after the war. They could barely afford for Werner to travel, let alone for Mady to accompany him.

But Mady was right, Werner rationalized. She should have the opportunity to meet her grandparent. And when would another chance present itself?

Frustrated by the dinner conversation and upset with the constant diet of liver and onions, Mady cried in her room. It wasn’t easy being the child of immigrants. At school, she was too German to be completely accepted. And at home, she was too American for a family trying to hold onto their heritage and their traditions. Especially her mother’s.

Eventually, Werner overruled Lilo’s resistance and agreed Mady should travel to Germany to meet her grandmother. They would go in August, before the school year started.

Airplanes did not fly non-stop routes. Flight plans took them from Cincinnati, to New York City, to Newfoundland, to Ireland, to Amsterdam, and then to Frankfurt. After landing in Frankfurt, Werner’s nephew-in-law Hans Albert picked them up from the airport and drove them to Braunfels, a small village in western Germany.

Braunfels was a quintessential German village. A spa town of roughly 10,000 (estimated population, 2020), Braunfels is situated at the foot of Braunfels Castle and features quaint Alpine architecture and cobblestone streets. Mady and Werner stayed at the Schlosshotel, where she remembers eating the best strawberry preserves on muffin bread for breakfast every morning.

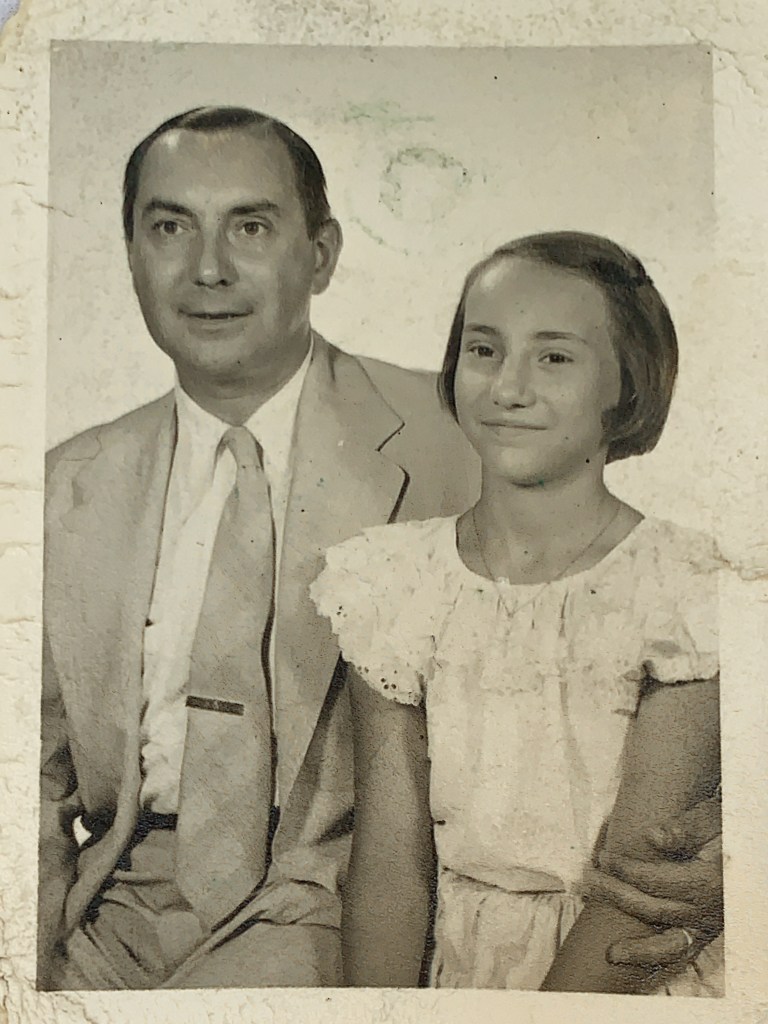

Mady carried an orchid to meet her Oma. Elisabeth was kind, but not necessarily warm as Mady had anticipated a grandmother to be. Werner was all smiles as he brightened to introduce his daughter to his mother. It was good to see her again.

Living with Elisabeth was Tante Luise, the wife of Werner’s older brother Paul. Although Luise and Paul were separated, Luise had moved in with her mother-in-law as a caretaker. Mady recalled Luise walked with a cane due to a “bum” leg. According to family stories, her knee cap had been broken from being harassed and assaulted, punishment for being married to a Nazi.

Oma Elisabeth, it turned out, was as strong willed as her own mother. And very German, meaning not as affectionate as Mady had hoped. She often clung to her grandmother, hoping to be doted upon with affection.

They celebrated Elisabeth’s birthday with her favorite dinner, eel. Considered a delicacy in Germany, this was a strange meal to Mady, although she was accustomed to a variety of food. (Lilo was a fine chef and often prepared meals such as lung hash and beef tongue.) Joining the family were Luise’s daughter Inge, son-in-law Hans Albert, and grandson Axel (age 3). Inge doted upon her uncle and little niece, the only members of her extended family.

Mady recalls going for afternoon walks with her grandmother around the village and being fascinated how the woman was greeted as “Frau Oberst” (Madame Colonel). Werner’s father had been mortally wounded in WWI, and it was customary for a woman to be recognized with the title of her husband. After their walks, Oma would snack on tomatoes in a sugar bowl, before retiring to her bedroom for a nap. Mady would sit by her feet while she snacked, getting as close as she could, then play quietly. Since Werner worked nights, quiet play was not an uncommon skill.

One day, Hans Albert took Werner and Mady on a tour of the nearby town Gessen. Driving through town, Hans Albert suddenly stopped the car and said, “Das ist Paul.”

Paul, Werner’s estranged and only living brother, and Werner had not seen each other in over ten years and were not inclined to have a friendly dialogue. Paul was six years older and had graduated from the Prussian Military Academy. Following in their father’s footsteps, Paul joined the German Army during the war. And he became a strong supporter of the National Socialist party. He was a former Nazi.

But Paul was also the black sheep of the family. He wasn’t smart or ambitious like his older brother Fritz, nor was he the amiable favorite like his younger brother Werner. When the Second World War ended, Paul was interred in a POW camp in Italy after being captured in northern Africa. Upon his release, he was rumored to have stayed in Italy for some time with a mistress, while his wife lived with and cared for his mother.

Werner, always amiable, took Mady’s hand and crossed the street to meet Paul. After a few brief sentences, Paul looked down and said, “Ist sie dast kleine Madchen?” Is that the little girl. Werner said yes, and introduced his daughter to his brother. After a few more coolly stated sentences, the brothers parted ways.

Mady and Werner stayed in Braunfels nearly two weeks. Werner wanted to go to Charlottenburg, a suburb of Berlin, to visit his father’s grave. But Mady was too afraid to travel to Berlin, for fear the Russians would kidnap them.

Soon, Werner and Mady returned home on a flight similar to what brought them over.

Six weeks later, Oma Elisabeth fell and broke her hip. She died of pneumonia a few days later.